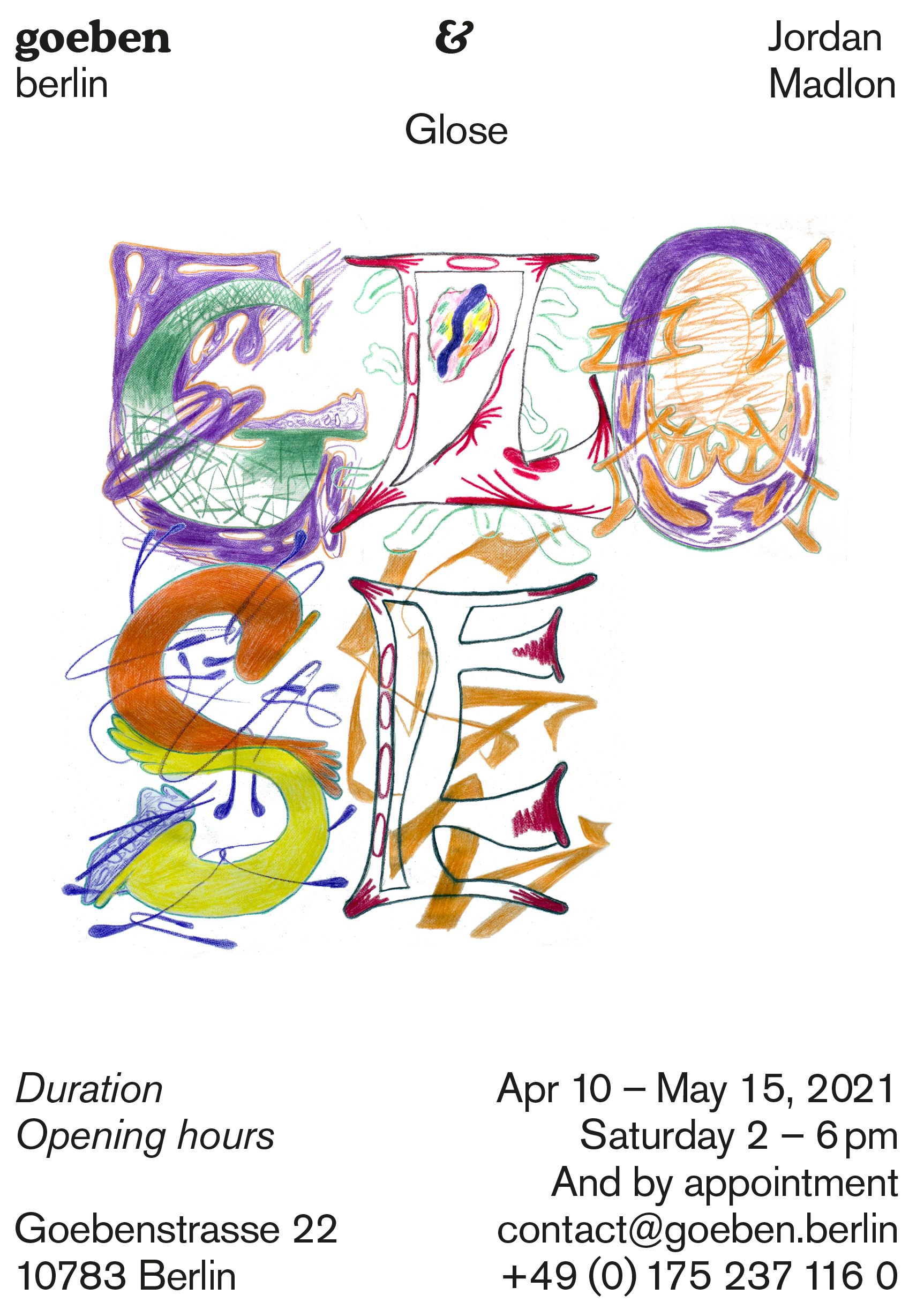

With his works, Jordan Madlon demonstrates a rejection of the rectangular form. Since the rectangle is historically associated with the frame, it marks a clear boundary and is thus itself the form of rejection and enclosure. In the exhibition „Glose“, the rectangle is limited to architecture, in which the artist embeds his irregular shapes. His lines are rather driven by a desire for opening and elasticity.

Opening and elasticity are central to Jordan Madlon‘s exhibition, as he enables the irregular shapes to pass through a variety of different qualities. This can be viewed in two exhibited shapes. I call them Ductus (as in „À propos de l’expressivité“) and Hatching (as in „Shablone“). The ductus, on the one hand, signifies the expressive power of brushstrokes, which the artist keeps in check as a motif, rendered by no less expressive pencil lines. Thus the drawn ductus is already an opening. From drawing to painting, from form to architectural format, from the current situation to art history (e.g. Roy Lichtenstein‘s „Brushstroke Paintings“, a kind of gloss on Abstract Expressionism). The hatching, on the other hand, is an essential shape that Aby Warburg would have called a serpentine line. As such it bundles the speed of zigzag with the joy of lurching. In “Glose” Jordan Madlon repeats the hatching at various spots through technical reproduction (stencilling, cutting, etc.) thereby opening shape to space. Consequently, the opening to space transforms the hatching. It is placed on a puckered support, occupies the wall and is three-dimensionally executed in fabric, slumping slightly due to its weight. For “Déplacement(s)”, the artist cut out the hatching shape from a colourful patterned fabric and sewed it with an uneven volume. A constellation, which reminds us of cave paintings: The irregular shape encounters the relief of an irregular ground. This reference captures also the site-specificity of the exhibition. „Glose“ is a self-commentary by the artist as well as a commentary on the spatial premises of goeben. The shape of an œuvre is placed on the moulded ground of an architecture. „Porte“, for example, follows the lines of the given surroundings, building a wall that one can walk through, and is ultimately a projection surface for the grisaille of a vague memory. Hence, on this surface the artist repeats shapes from his earlier works and those that (like the hatching) can be found elsewhere in the exhibition.

Jordan Madlon endows his shapes with elasticity that provides an opening between solidity and adaptation. They incorporate a tight association of image and material while at the same time being outlined by the fluidity and speed of mind. The exhibited shapes thereby traverse a multitude of different layers: (art) history, language (Deleuze spoke of concepts that are cut to size), the different places of exhibition, their own body of work, the techniques of production and colours of their appearance. This passage through different layers should not be mistaken with the indecision of our current image use. Digital images appear in a wide variety of formats, materials or colours and are accordingly perceived in various ways. The shapes in Jordan Madlon‘s exhibition, however, neither reject external circumstances nor can they be deformed randomly. The artist counters the arbitrariness of current image practice with the thought and form of elasticity. Elasticity includes as much the ability to respond to the actual circumstances as it includes the ability to shape it.

By Manuel van der Veen,

for the exhibition GLOSE at Goeben, Berlin in 2021

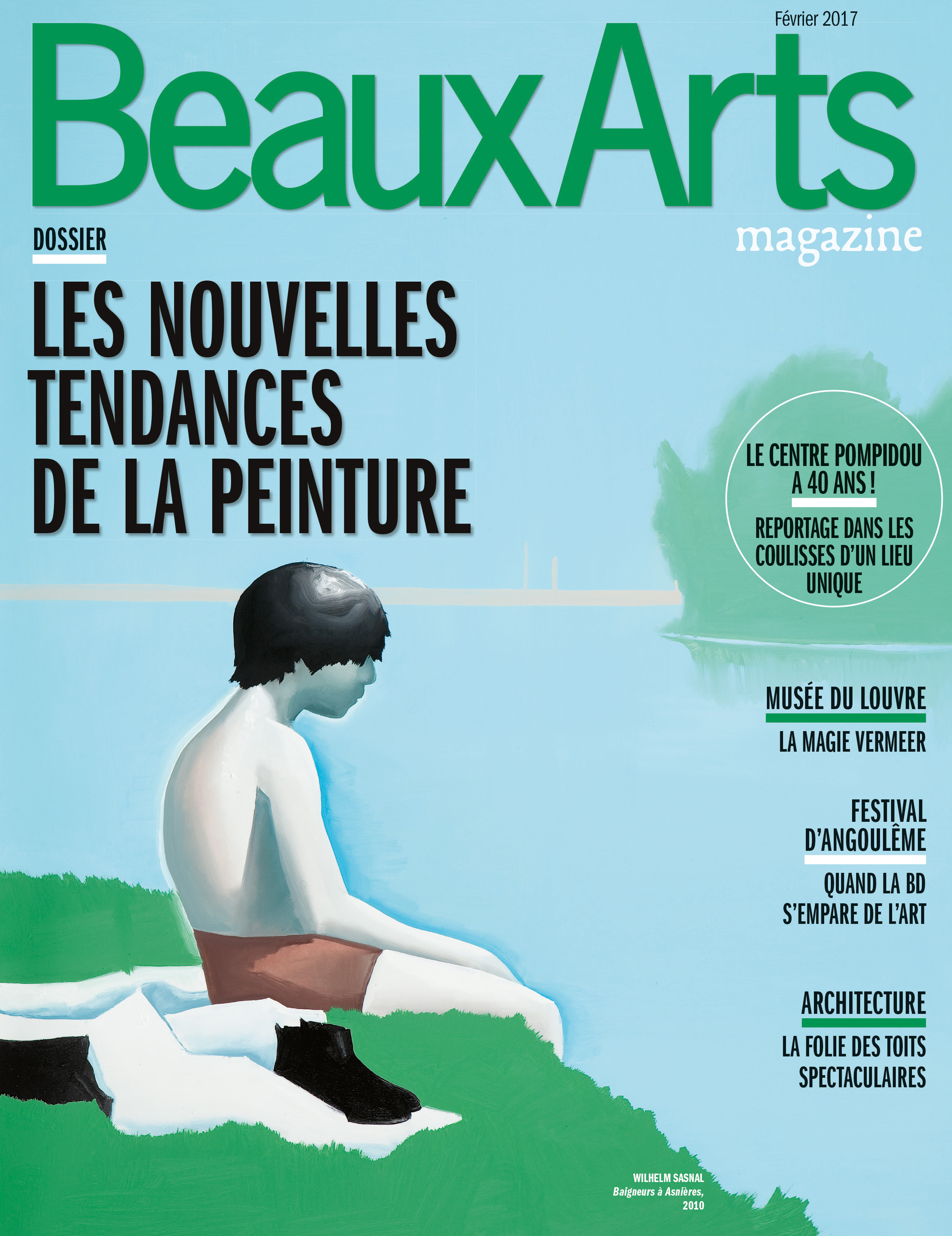

Par période, le tableau ne s’en laisse plus compter par la peinture. Il ne se réduit plus à cette simple surface plane tenant dans les limites d’un cadre régulier et traditionnel. Or cet objet pictural, ou cette peinture tentée par la mise en forme de son support, se décline sur tous les tons. Il y eut les sobres shaped canvas d’un Ellsworth Kelly prêtant à ses tableaux la découpe d’une aile de voilier, puis ceux compliqués de Frank Stella, hérissant la toile de panneaux courbes qui rebiquent et se mordent entre eux. Il y eut dans les années I970 en France, cette période (celle de Supports/Surfaces) où le châssis se refusait à tenir la toile, préférant la laisser traîner au sol pour s’exhiber lui, son propre et étique squelette, et puis plus récemment les toiles de Philippe Decrauzat et de Blair Thurman, creusant un trou en leur centre et reléguant la peinture à la périphérie d’un trou béant. C’est dire si le shaped canvas n’est pas un genre en soi, plutôt une modalité de la peinture supportant toutes les tonalités, de la plus dépressive ou pessimiste à la plus jubilatoire et rayonnante, ce dernier penchant étant cette année le plus amendé. Par Jordan Madlon et ses petites toiles découpées qui prennent des formes aimablement bonhommes et cartoonesques, tout en restant abstraites, de même que celles, longilignes et entrelacées, pastels et relâchées, de Justin Adian, en passant par les peintures de Ruth Root, qui, à 50 ans, fait presque figure de doyenne. Mais on a peu vu en France ses tableaux ressemblant à des plans cadastraux, des schémas d’urbanistes ou, mieux, à ces cartes, diagrammes ou représentations graphiques de données statistiques, démographiques, économiques… qui étirent les représentations géographiques traditionnelles. Donner du monde une représentation plus synthétique, moins réaliste (dans le trait, la composition ou la palette), c’est aussi ce vers quoi tendent d’autres jeunes artistes qui, sans du tout attenter aux limites régulières du tableau, forcent pourtant le trait de la déformation des contours de la réalité. Amélie Bertrand livre ainsi des décors aux perspectives déformées et aux couleurs acidulées trempés dans un bain de Photoshop tandis que le Suisse Nicolas Party ou bien l’Allemand Andreas Schulze réduisent leurs personnages et les objets courants à des espèces de silhouettes géométriques, avatars des paysannes formalistes de Malevitch et des robots humanoïdes des jeux vidéo.

Dossier Nouvelles tendances en Peinture,

par Judicaël Lavrador,

Beaux Arts Magazine n°392

L’homme habite en peintre

Ce travail pictural commence par une approche formaliste de la peinture. Formes géométriques, gestualités, réduction de la palette colorée; m’apparaissent alors comme des éléments nécessaires à la compréhension de la peinture. Je privilégie l’agencement à la composition et le mur à un support mobile.

La manipulation de ces formes géométriques, de ces gestualités isolées sur le mur, m’ont conduit à m’interroger sur les limites de leurs espaces d’inscriptions. Où commence la peinture et où se termine-t-elle? Et comment reconstituer l’espace de réserve?

Ainsi la peinture je la pensais comme un insert dans un lieu et en situation plutôt qu’in situ. La série des (in situ) prend en charge ces considérations spatiales, ce sont des éléments qui se présentent à la périphérie du mur et qui ne sont présentables que dans la mesure où l’angle, la position par rapport au mur, en somme sa situation spatiale est adéquate. Cette recherche d’autonomie de la peinture, vis-à-vis du support et du lieu d’inscription m’amène à réaliser des objets picturaux, mais sans pour autant en révoquer l’espace qui l’accueille. Ils se présentent en tant que segments, mètres étalons, gestualité de la peinture même rendu par découpage, et collage de papier à motif ou de papier de soie coloré me permettant d’aborder la surface picturale de façons autonome.

Cependant toutes ces mesures me permettent d’envisager d’autres formes possibles pour la manifestation du tableau, ainsi il n’y aurait plus un objet dans un espace mais bien un espace dans un autre. Les isolements que j’ai pu opérer constituent en somme des localités de la peinture, qui investissent l’espace, qui l’habite d’une certaine façon. Si bien que l’espace envisagé comme totalité — picturale — est rendu par ce travail de façons parcellaires.

L’homme habite en peintre,

par Jordan Madlon